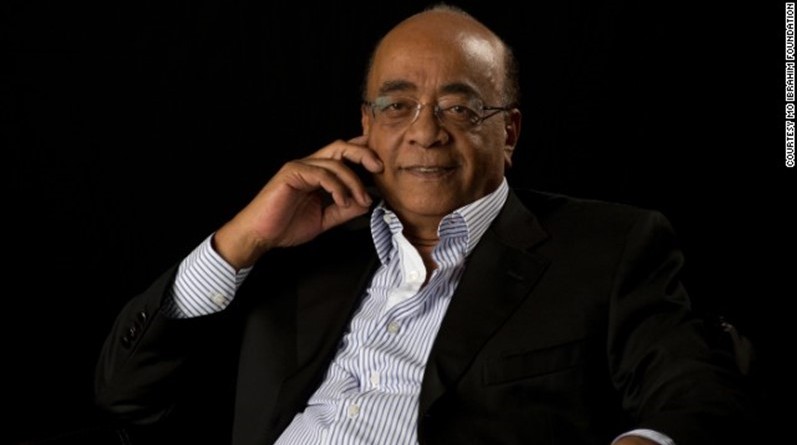

Meet Mo Ibrahim, the billionaire who brought cell phones to Africa – CNBC

The two were at an event at the University of Ghana and it was Ibrahim who people crowded around, not Bono, whose band has sold around 150 million records. “I remember being trampled by a lot of the students in the university there. They hadn’t a clue who I was,” Bono said. “And I was cool … But at one point, I think one of them came up and said: ‘Would you take a photograph?’ And I … was kind of relieved. And then they handed me the camera and put their arm around Mo. So, he’s a superstar, he’s the rock star in the room.”

Bono and Ibrahim met around 15 years ago at an event in Senegal, when Ibrahim was “excoriating” the aid community. “He was explaining to people that it’s not the fight against extreme poverty that matters. It’s the fight to get people in the direction of prosperity. We had to think about things differently. Aid was critical, but the dignified response was to be involved with people in their lives, and in their businesses,” Bono told “The Brave Ones.”

Why does Ibrahim attract such fame? Well, aside from starting African mobile network Celtel in 1998 and selling it for $3.4 billion in 2005, he founded a prize for leadership in Africa and his Ibrahim Index ranks African countries in terms of how well they are governed, holding political leaders accountable for all to see.

“Because he takes on leaders, sometimes in ways that surprise all of us, he’s become a hero to people at the grass root level,” Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, the former president of Liberia, told “The Brave Ones.” “Because they know that he can challenge the leaders in their country … not only quietly, but also openly,” she said.

Ibrahim does not hold back with criticism of corrupt governments or outsiders’ perspectives of the continent.

“Unfortunately, when you ask Europeans or Americans about African leaders, the first thing they mention, ‘Oh, it’s (former Ugandan president) Idi Amin, it’s Mobutu (Sese Seko, a former Congolese dictator) … you always remember our bad apples,” Ibrahim told “The Brave Ones.”

“We have some decent leaders. Nobody knows about them. Because they’re not in the news … We have a few criminal guys, but not many. We have a lot of good people. So, we need also to change the picture.”

Ibrahim had an early ambition to be a scientist. “As a kid, the posters in my room were (Albert) Einstein, Marie Curie — and the inevitable romantic Che Guevara with the beret. That was in the 60s.”

After a degree in electrical engineering at the University of Alexandria, he worked for Sudan’s telecom department before going to the U.K., gaining a master’s degree from the University of Bradford and a PhD from the University of Birmingham. In 1983, he joined British Telecom (BT) as technical director, tasked with designing its mobile network, Cellnet (now O2).

“The total size of the industry at the time was £10 million ($12.9 million) a year. I was fascinated by the concept of mobile communication and mobility, because that was a new concept. Up to that time, telecommunication was about communication between two fixed points … Then the work started on the issue of, can mobile become really a popular kind of network? It was really for emergency services and police, fire brigade.”“Because of my (up)bringing, because of my social background … we assume businessmen are crooks or people involved in funny stuff.”

But after around six years, Ibrahim became frustrated. “And I come from (an) academic background, but I was appalled about … the bureaucracy, and it was strange, because I’m not supposed to be the business person; I’m supposed to be the technocrat … So, what do you do when you get fed up working in a large company and (are frustrated with) the bureaucracy? I said, ‘OK, I’m going to be a consultant.’”

Ibrahim never expected to go into business. “Because of my (up)bringing, because of … my social background … we assume businessmen are crooks or people involved in funny stuff. We respect professions, you know. You need to be a doctor, an engineer, to earn honest money and to do (the) right work, but guys involved in wheeling and dealing, we are suspicious of that,” he said. “That was my upbringing, in a way. I really wanted to work (in) research, science and I ended up being an accidental businessman, actually

He started his consultancy, Mobile Systems International (MSI), from his home in a north London suburb. “We became the largest independent technology company in Europe, and I had to learn how to run all this, and … I had no business training whatsoever … But really the most important thing is just common sense … And never (be) afraid of saying: ‘I don’t know.’” Ibrahim still encourages his managers to ask if they don’t know something. “You need to raise your hand and say, ‘Sorry, explain to me, what is this about?’”

Ibrahim sold MSI to telecoms group Marconi for a reported $618 million in 2000. “Because I’m not a businessman, I did things completely different. I insisted everybody in the company must be a shareholder. And that was (a) long time before (share) options … became popular,” he said. Around 33% of the company’s shares were owned by engineering and software staff rather than senior management, a fact Ibrahim is proud of.

Part of the problem was the perception of the continent. Ibrahim recalls a contact he approached for investment in Uganda, which was offering free telecom licenses. But his friend’s response shocked him. “’Mo, you want me to go to my board and advise them to invest in Uganda? This country, you know, they have this terrible man, Idi Amin, running the country.’ I said: ‘Excuse me, Idi Amin left 15 years ago’… That really was a wakeup call for me … If that was the perception of Africa, no-one’s going to invest in Africa.”

The opportunity was huge: In 1998, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), for example, had a population of around 55 million, but only 3,000 phones, Ibrahim wrote in a 2012 article for the Harvard Business Review (HBR).

Even though Ibrahim still considered himself a “techie engineer” rather than a business person, he could see that developing mobile communications in Africa was “too big an opportunity to pass up.” But there were hurdles beyond the negative perception of the continent: Funding, credibility as a network operator (MSI was a consultancy) and a lack of infrastructure.

“I have to put in the microwave (technology), the fiber … to connect the power to the exchanges … A major (challenge) … is the power. So, we have to put (up) all these thousands of radio towers, but they need power, 24 hours. This was not available, so I have to have a generator in every tower. Then I need to have a backup to the generator, and then I need to have batteries for emergency. Then I need somebody to go every morning to supply fuel, to check the water levels. Now these towers can be on top of hills … There’s not good roads,” Ibrahim told “The Brave Ones.”

Investment was also a problem. “In a capital-intensive project like mobile networks … I need to build the network first, before I get one cent in revenue. Before anybody makes a call, I need to have the infrastructure made,” he explained. Typically, banks will loan more than 50% of the upfront costs, but none would provide funding for the network Ibrahim named Celtel. Eventually, Ibrahim had to offer the assets of the whole company as security for a loan, he wrote in HBR.

As well as a lack of infrastructure, the company had to deal with war in Sierra Leone and poor political relations between some countries. It took two years to negotiate with the governments of the DRC and the Republic of the Congo to allow a wireless link between the two countries (previously, calls were routed via satellite through Europe). There was also the issue of corruption — Celtel refused to bribe government officials when applying for licenses to operate, insisting that its whole board signed off on expenses over $30,000.

It also had to work differently in African countries’ developing economies, making its network available to customers who didn’t have bank accounts or couldn’t afford monthly contracts by selling scratch cards for small amounts of local currency. On the back of Celtel, other businesses sprang up: Retailers selling those scratch cards in small kiosks, subcontractors building the network and logistics businesses servicing the telecom towers.

By 2004, Celtel had reached $614 million in revenue. By 2005, Celtel was operating in 13 countries and had more than 5 million mobile subscribers and was considering an initial public offering (IPO) to raise further cash. After companies found out about the possible IPO, Celtel had several acquisition offers, and eventually sold it for $3.4 billion in 2005 to the Kuwait business Mobile Telecommunications Company (now Zain, which sold it to Bharti Airtel in 2010).

The Ibrahim Index

He didn’t want to simply provide handouts. “I know a lot of wonderful people doing great things … Bill Gates and Melinda are doing a wonderful job … Giving blankets, baby milk, family planning. My view is just slightly different … why (do) African people need (aid) in the first place? Why (do) we need philanthropy?” he said.

“Africa should be rich, because we are a very rich continent. We’re a huge continent. We have all these resources … so why are we poor? The answer was clearly the way we run our countries. It is the poor governance. It is the poor management of our resources — material and human.”

In 2007, he started publishing the Ibrahim Index of African Governance, measuring the continent’s 54 countries’ performance across categories including security, human rights, economic opportunity and welfare.

“Governance is about delivery of public good(s), delivery of education, health, safety, security … Do we have courts which are functioning? Do we have decent juries? Do we have judges, are they independent judges really? Poor people, people who live in rural areas, do you have access to justice? Education services, health, infrastructure, clean water, electricity, all these things have to be done by the government or facilitated by the government to get the private sector to do it,” he told “The Brave Ones.”

Seventy-two percent of Africans now live in a country where governance has improved over the past decade, according to 2018’s index. But it also showed that the decade was one of “lost opportunity” in terms of economic development, and that the growth of the working age population is outstripping financial gains.

“We need to manage this bulge in population and we need to find a way to create jobs, create investment … In the next 10 years Africans of working age will increase by 30%. Will our job market increase by 30% over these years? … That is a challenge for us,” Ibrahim said in a video on his foundation’s website.

Kenya (ranked 11), Morocco (15) and Cote d’Ivoire (22) improved the most in the index over 10 years. Kenya did particularly well on its business environment, including elements such as the efficiency of its customs procedures and the absence of bureaucracy, while Morocco scored well for accountability of its government and public employees and poverty reduction efforts.

Mauritius (1), Cape Verde (3), Ghana (6) and South Africa (7) remain relatively unchanged over the period. Countries toward the bottom of the list that have seen increasing deterioration include the DRC (47), Equatorial Guinea (48) and Libya (52).