The world finally has a malaria vaccine, Now it must invest in it by Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala

I vividly remember the day I learned a harsh lesson in the tragic burden of malaria that too many of us from the African continent have endured. I was 15, living amid the chaos of Nigeria’s Biafran war, when my three-year-old sister fell sick. Her body burning with fever, I tied her on my back and carried her to a medical clinic, a six-mile trek from my home.

We arrived at the clinic to find a huge crowd trying to break through locked doors. I knew my sister’s condition could not wait. I dropped to the ground and crawled between legs, my sister propped listlessly on my back, until I reached an open window and climbed through. By the time I was inside, my sister was barely moving. The doctor worked rapidly, injecting antimalarial drugs and infusing her with fluids to rehydrate her body. In a few hours, she started to revive. If we had waited any longer, my sister might not have survived.Advertisement

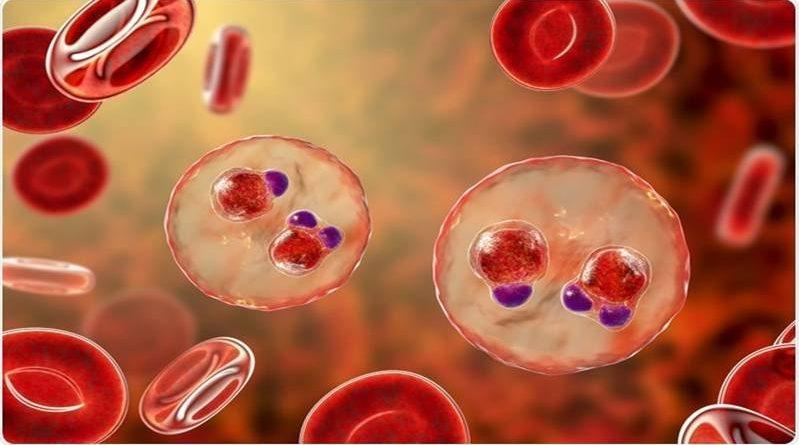

Thinking about that day, I consider how far we have traveled in the fight against malaria, with the recent historic announcement from the World Health Organization (WHO) recommending the world’s first malaria vaccine (RTS,S) to reduce illness and death across regions where children are at risk. As part of a package of interventions, tailored to local malaria conditions, the vaccine could save tens of thousands of young lives every year – especially among the most vulnerable, as my little sister was.

Since 2019, more than 800,000 African children have had at least one dose of the RTS,S vaccine as part of a pilot in Ghana, Kenya and Malawi. Now, with the right investment, millions more children could be immunised and grow up with less malaria, fewer hospitalisations and healthier lives.

Malaria is emotional – it strikes suddenly and kills our children. But I am an economist, so I put emotion aside to consider whether the vaccine is a good investment.

Malaria impoverishes countries. A 2001 study estimated per capita income levels in malaria-endemic countries to be 70% lower, and malaria results in $12bn (£9bn) in lost productivity around the world each year. Some countries spend up to 40% of their public health budget treating the disease. This is the stark divide that malaria creates every day in Africa and one that a malaria vaccine can help close. Analysis of data from 180 countries demonstrates a clear link between a reduction in the burden of malaria and faster economic growth.

I urge the global health community to invest on a robust scale so that we may reap the fruits of this breakthrough

Malaria disproportionately affects the poor and hampers the economic development of communities. Malaria has pushed many a working family into poverty. So yes, as an economist, I can say that investment in a malaria vaccine is money well spent – for economic development, for poverty reduction and to reduce inequities.

I applaud the governments, the WHO, its partners and the funders that have supported the pilots that have brought us to this point. I was honoured to chair the board of Gavi, the vaccine alliance, in 2019, when we made important decisions on efforts to bring this vaccine forward. Today, in a different capacity but with the same passion, I urge the global health community to again be bold and invest in the malaria vaccine on a robust scale, so that we may reap the fruits of this breakthrough for children’s health.

My sister is now a doctor, working to save the lives of others, and the mother of three children. Saving children from malaria is about protecting Africa’s future. Despite progress against the disease, millions of Africans have died from malaria since 2000, most of them about the same age as my sister when she became sick. They will not have a chance to become doctors, teachers, farmers, computer programmers or play any other role, or to have and care for their own families.

But with the introduction of the world’s first malaria vaccine, and continued investment, we can curb this terrible disease. The RTS,S vaccine is a cost-effective new tool, something concrete we can act on now to give millions of boys and girls the chance to contribute – and ensure Africa’s economic progress is no longer slowed by malaria.

As the world witnesses tremendous inequities in access to vaccines, and we explore ways to bring vaccine development knowhow and capacity home to Africa, it is our collective responsibility to invest in the malaria vaccine now in our hands, and ensure that it reaches those who need it.

- Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala is the director-general of the World Trade Organization

SOURCE. TheGuardian