Bird Flu sweeps through the world, infecting birds, animals and humans – a BBC Story / Documentary

Bird flu is decimating wildlife around the world and is now spreading in cows. In the handful of human cases seen so far it has been extremely deadly.

Lineke Begeman’s fingertips are still experiencing numbness after a challenging expedition. In March, the veterinary pathologist participated in a global mission to Antarctica’s Northern Weddell Sea to investigate the spread of High Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI), the virus that has now encircled the world, leading to the outbreak of bird flu.

Performing autopsies on the frozen bodies of wild birds collected by the team, Begeman played a crucial role in determining whether the birds had succumbed to the disease. Despite the harsh conditions and remote location, far from her usual workplace at the Erasmus Medical Centre in the Netherlands, this systematic monitoring could serve as a crucial early warning system for the global community.

“If we fail to assess the extent of its transmission now, we will be unable to inform the public about the repercussions of neglecting it at the onset,” Begeman explains to BBC Future Planet. “I envision the virus as an explorer venturing into new territories and bird species, and we are trailing behind it.”

While the number of human cases remains relatively low, the virus has proven to be extremely lethal, with a mortality rate of over 50% among those infected.

Where does bird flu come from?

Furthermore, the impact on wildlife has already been catastrophic. Ever since the identification of the H5 strain of avian influenza and its variations, over 500 million farmed birds have been slaughtered. The estimated number of wild bird deaths is in the millions, with approximately 600,000 occurring in South America since 2023 alone. However, these figures could potentially be much higher due to the challenges faced in monitoring. Additionally, at least 26 species of mammals have also been infected.

In the Northern Weddell Sea of Antarctica, Begeman and her colleagues collected samples from approximately 120 carcasses belonging to various species, including several Antarctic fur seals. The virus was detected at four out of the ten sites they visited.

This was not the first instance of bird flu being detected on this remote continent. The initial case was reported a month earlier, in February 2024. However, Begeman’s team was the first to confirm its presence in this specific region. She believes that their multidisciplinary approach was also the first of its kind to systematically determine the extent of its spread in Antarctica.

“The moment we discovered the initial evidence of this destructive virus, which acts as a serial killer, in such a pristine and bird-abundant area, we realized the impending disaster and it became truly disheartening,” expresses Begeman.

Already considered the most severe outbreak of bird flu in wildlife to date, scientists like Begeman are now in a race to track its progression. Their aim is to gain a better understanding of how it spreads among humans and ultimately find ways to prevent its further transmission.

China’s southern Guangdong region is a diverse landscape of lakes, rivers, and wetlands. These aquatic environments provide an ideal habitat for water birds, which naturally carry low pathogenic avian flu. In 1996, a farmed goose in this region became the first bird in the world to be diagnosed with a new, highly pathogenic strain of the virus called H5N1.

The classification of bird flu as low or high pathogenic was initially based on chickens and did not apply to other bird or mammal species. While low-path avian influenza is not fatal in wild birds and only causes mild illness in chickens, it can mutate into highly pathogenic strains in poultry, leading to severe disease and often death.

According to Thijs Kuiken, a comparative pathologist at Erasmus University Medical Centre in the Netherlands, it is not surprising that the highly pathogenic virus was first detected on a poultry farm. He explains that high pathogenic avian influenza is typically a poultry disease and does not occur in the wild. What is unusual now is that this particular strain has spread to wild birds, enabling its global transmission.

Although wild birds have played a role in spreading the virus beyond China, Kuiken emphasizes that “people are the real problem.” He specifically points to the increasing demand for farmed meat as a significant factor.

In 1996, when the outbreak began, there were approximately 14.7 billion poultry birds worldwide, mostly chickens. Today, that number has doubled. Kuiken highlights that poultry currently accounts for over 70% of all avian biomass globally.

If current trends in poultry farming continue, Kuiken warns that other highly infectious pathogens will continue to spread among the remaining wild bird populations. For example, house finches are highly susceptible to a bacterial poultry disease called Mycoplasma gallisepticum. Additionally, virulent strains of Newcastle disease are crossing over into various species, including parrots and macaws. “High-pathogenic bird flu is just one of the threats,” Kuiken concludes.

How did bird flu spread around the world?

- H5N1 timeline

- 1996: detected in poultry in Guangdong, China

- 1997: first human deaths in Hong Kong

- 2005: Spilled over into wild birds in a major way. New strains emerge.

- 2020: A strain emerges that can sustain in wild bird populations year-round

- 2020-22: Becomes endemic in wild bird populations

- 2021: Arrives in North America

- 2022: Detected in South America

- 2024: Confirmed in Antarctica

By 2005-06, the virus had spread to wild birds and had reached Europe, Africa, and the Middle East. However, it was not able to sustain itself in these populations for long due to various factors such as limited spread in wild birds, low survival rates in water, and some birds developing immunity. This containment was disrupted in 2020 with the emergence of a new strain of H5N1. This strain was able to persist year-round in wild bird populations and spread rapidly during the breeding season when birds congregate in large numbers.

In late 2021, the virus was introduced to the New World through Canada’s eastern Newfoundland province. A black-backed gull, discovered ill in a pond, was taken to a wildlife rehabilitation center where it succumbed the next day. Subsequent tests revealed it was infected with H5N1. Shortly after the gull’s death, a poultry farm reported increased mortality rates, and autopsies confirmed the presence of the virus.

The absence of evidence linking the farm to imported poultry from Europe supported the hypothesis that wild birds’ migration paths serve as the primary long-distance carriers, as explained by Kuiken. There were some exceptions, such as the transmission of infected turkeys from the UK to Europe.

By 2022, bird colonies from the UK to Israel were experiencing mass die-offs. In October 2022, the virus was identified in wild birds along the west coast of Peru and Chile. It then spread down the coast before returning up the east, reaching the Falkland Islands and South Georgia – the gateway to the Antarctic.

The virus has taken different paths along this route, infecting a diverse range of mammals, including 21 species in the US alone. This cross-species transmission has increased the chances of both human contact and mammal-to-mammal spread.

As of 16 April 2024, HPAI has been confirmed in dairy cows on 26 farms across the US, spanning from Texas to Michigan. While some cases may have been caused by wild birds, there have been instances where long-distance transport of cows has been linked to the infection. Currently, there has only been one reported case of cow-to-human transmission, and it is believed that the virus would need further mutations to easily spread among people.

However, farms can create conditions that facilitate the spread of diseases, providing new opportunities for adaptation. Gregorio Torres, the head of the science department at the World Organisation for Animal Health, emphasizes the importance of farmers being cautious, as while wild birds can transmit the virus, domestic farms can amplify its effects. He compares it to avoiding crowded public transportation when you are already sick.

A positive aspect is that birds in New Zealand and Australia have been unaffected so far. Although these countries are part of the East Asian-Australian migration route, the visiting birds are primarily shorebirds or waders, which are less susceptible to the virus compared to waterfowl like ducks or geese, as noted by Kuiken.

How does bird flu spread to humans?

The current outbreak of H5N1 avian influenza has crossed species boundaries multiple times, infecting various mammals, including humans. However, the virus has not yet undergone significant evolution or mutation to facilitate easy transmission between the different mammals it affects. The initial cases in humans were documented in Hong Kong in 1997, and the global spread of the virus was relatively slow, with only 800 reported infections in the first 13 years, primarily affecting poultry and slaughterhouse workers.

The primary risk factor for contracting the virus was identified as contact with sick birds, their droppings, saliva, or feathers, although the exact method of interspecies transmission remains unknown.

Is bird flu the next pandemic?

In March 2024, a new, uncommon strain of the virus was identified in cattle. By April, a farm worker in Texas became the second person in the US to contract H5N1, marking the first suspected case of mammal-to-human transmission.

Subsequent confirmation of cow-to-cow transmission highlighted the potential spread of the disease through contact with unpasteurized milk, as stated by the US Department of Agriculture.

Scientists are unable to predict whether bird flu will escalate into the next global human pandemic, according to Torres. However, it is evident that the disease is persistent, necessitating preparedness. Torres emphasizes that each interspecies transmission signals an elevated risk, prompting swift action to comprehend and anticipate the virus’s evolution.

Torres further warns of the worst-case scenario where the virus adapts to mammals, increasing the risk of human-to-human transmission.

Diana Bell, a conservation biologist at the University of East Anglia in the UK, highlights bird flu as a potential candidate when questioned about the next human pandemic. She notes that there is already a pandemic among animals and birds (a panzootic).

Can we prevent bird flu in humans?

Experts suggest that stopping bird flu in wildlife is a challenging task due to the difficulty in preventing transmission. However, there are measures that can be taken to minimize the impact on both wild and farmed animals, as well as humans.

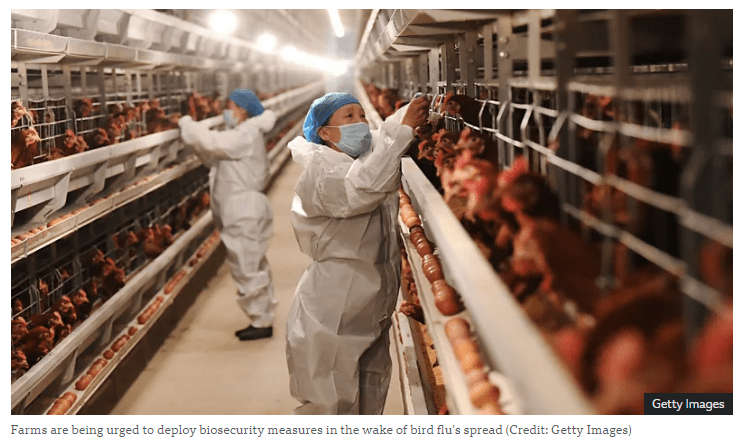

It is recommended that dead wild birds are not touched and reported to the authorities. Additionally, farms are advised to implement biosecurity measures, such as covering waste and reporting any signs of illness. The World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH) is advocating for compensation schemes to be in place for farms that are required to cull their animals.

The issue of vaccinating poultry is a topic of debate. While preventative vaccination has been proven to reduce outbreaks in high-risk areas, some countries are hesitant due to trade barriers that limit the import of products from vaccinated flocks. Despite the challenges, better surveillance can help mitigate the risks associated with vaccination.

In order to control and prevent future outbreaks of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI), global meat production practices may need to be reformed. This could involve implementing a cap on the global poultry population size and promoting more sustainable consumption habits. Europe, for example, currently consumes twice as much meat as recommended by global health authorities.

How badly is wildlife affected by bird flu?

HPAI has already become a global wildlife pandemic, according to Marcela Uhart, a veterinarian at UC Davis. She emphasizes that the conservation impact of this virus is unprecedented, with a scale of species and regions affected that has never been seen before.

One particular concern in Argentina, Uhart’s home nation, is the virus’s spread among wild mammals. Her research has shown that the virus is nearly identical in fur seals and sea lions, and many of the adaptations detected in these mammals were also present in a human case in Chile. Uhart emphasizes the urgency of detecting any further adaptation of the virus to spread between mammals.

The impact of the virus is not only worrying for humans in the future, but it is already devastating other mammals. During the 2023 breeding season, it is estimated that over 17,000 elephant seals died from the virus, including 70% of all the season’s pups. The fate of the adult seals that went to sea is unknown, and Uhart and her colleagues anxiously await their return this spring. If enough pregnant females come back, there is hope for recovery, but if not, or if the virus strikes again this year, the impact could be significant.

Urhart expresses the anxiety felt by everyone involved in this situation. Monitoring the population-level impact on wildlife is crucial, but unfortunately, there is insufficient funding for this important work. The current efforts are being carried out with limited resources.

However, the need for continued monitoring cannot be overstated. The removal of these species from the food chain could have far-reaching consequences for the entire ecosystem. The future is uncertain, and it is essential to stay vigilant.

How can we help wildlife cope with H5N1?

Reducing the various pressures on wildlife could potentially enhance their chances of survival as H5N1 emerges as a new threat to bird and mammal species. Climate change, habitat destruction, bycatch in fishing activities, overfishing, invasive species, and pollution – including plastics and pesticides – are all contributing to the decline in global biodiversity. Addressing these human-induced pressures may provide populations affected by HPAI with a better opportunity to recover, according to Richard Phillips, a seabird ecologist at the British Antarctic Survey.

Phillips’ research on albatrosses has demonstrated that fishing vessels implementing mitigation strategies, such as avoiding discarding fish while trawling and using bird-scaring lines, can significantly reduce seabird bycatch. Given the impact of bird flu on the vulnerable wandering albatross, Phillips is concerned about the species’ future unless the issue of fisheries is tackled.

As scientists monitor the spread of HPAI in wild populations and explore new detection methods, Begeman’s expedition marked a significant milestone by establishing a complete testing laboratory on an Antarctic-bound ship. Wildlife biologists would search for dead birds on foot, while others would sample apparently healthy animals. Their investigative work, akin to that of detectives, involved examining carcasses and fending off curious sheathbills in unexplored territories.

The objective is to gather data from remote locations worldwide to guide decision-making closer to home. For Kuiken, implementing policy changes to minimize risks in the poultry sector is a top priority. Additionally, vaccination, preventive measures, and conservation efforts could play a vital role in supporting birds and mammals during this outbreak.

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can’t-miss news, delivered to your inbox twice a week. SOURCE: BBC. Story by By India Bourke, Features correspondent