7 FAILED STARTUPS AND THE LESSONS LEARNED

In 2005 Evan Williams founded a podcast platform called Odeo. Unable to compete with Apple’s iTunes store, Odeo only went on to raise a Series A. However, Williams’ side project, Twitter, went on to become, well, Twitter.

In 1997 online dating and social networking site, SocialNet was founded with the intention of connecting individuals for professional networking, roommate matching, as well as dating. The platform unfortunately failed, but founder Reid Hoffman credits his failure with SocialNet as the basis for the success of LinkedIn.

Some of the best success stories start with failures. And with the Startup Genome Report citing that within three years, 92% of startups fail, maybe there’s something to learn before jumping into your own company. Let’s take a look at some common blind spots, FAILED STARTUPS, and how we can avoid them.

We reflect on seven promising startup stories that ended in failure to see what we can learn from them and their mistakes.

1. Shyp, raised $62.1 million

The freshest of the failures on this list, Shyp, was founded to make shipping items globally as easy as “two taps on a smartphone.” Only a few months after launch, Shyp received coverage from the New York Times and heavy investor interest. It was clear the pain points they were tackling resonated with a large audience.

Rapid growth bore them comparisons to Uber, and as CEO and founder, Kevin Gibbon, explained in his blog post outlining the closing of Shyp, he explained:

“Uber had transformed the way consumers thought about transportation. We could do the same, I was told. And I believed it. The numbers told a story and I became fixated on that story.”

As consumer growth slowed, Shyp was unable to keep up with its own growth. Rather than re-adjusting strategy from consumer customer acquisition, Shyp trudged onwards. Although Gibbon did eventually take the advice to slow down growth and re-orient the company, by that time it was too late.

Early mistakes hindered the company’s potential for a successful future, and the “growth at all costs” mentality eventually led to Shyp’s demise.

Lessons learned: Don’t hyper-focus on vanity metrics. Act quickly and pivot early if needed.

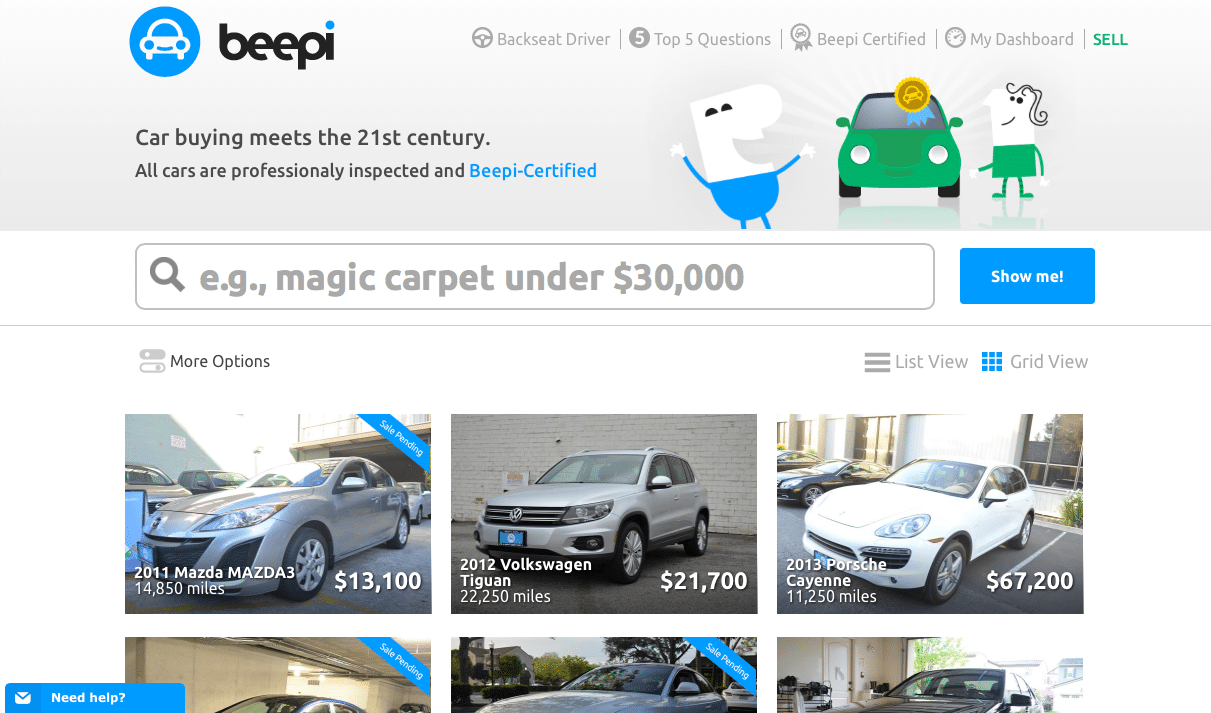

2. Beepi, raised $149 million

Beepi’s used car marketplace made a big splash when it was first founded. In a world of exploding on-demand marketplaces, Beepi’s future looked bright to consumers and investors. In 2015, Beepi secured a hefty $60 million Series B funding round.

Considered a classic example of a company with a “good idea and bad execution,” Beepi’s high burn rate led to the company’s demise. Leadership was notorious frivolous, with TechCrunch reporting that Beepi’s executives were going through $7 million monthly due to “grossly high salaries” and spending on frivolous extras like a “$10,000 sofa” for an exec’s private office.

The founders may have also been set on raising too much money too soon and were far too aggressive when negotiating for a higher valuation. Reports also say leadership was also known to micromanage decisions, not giving their employees the chance to act quickly and learn. Struggling after an unnamed strategic Chinese investor pulled out its support, Beepi was forced to lay off its 180 staff members.

Beepi blew through their $149 million in funding, merging its remaining parts to Fair.com, later reported an attempt to repay creditors.

Lessons learned: Be cautious, not cocky – money does run out.

3. Juicero, raised $118.5 million

Founded in 2013, Juicero was known for their $699 wifi-connected luxury juicer that required proprietary juice packs. Original founder, Doug Evans, compared himself with Steve Jobs in his mission for juicing perfection, explaining how his juice press had the force to “lift two Teslas.” Tech blogs labeled Juicero, the “Keurig for juice.”

Although the CEO, Jeff Dunn, former president of Coca-Cola North America, argued that the Juicero was “much more” than just a juicer, the public seemed to disagree. When Bloomberg released a video that showed that their juice packets could be squeezed by hand just as quickly, if not faster, consumers were dissuaded by the seemingly obsolete and large machine. Investors also expressed that the device was bulkier than originally thought.

Responding to the negative press, the team cut the cost of its machine to $399.

After shifting resources to lower the price of the machine and their juice packs, Juicero shut its doors 16 months after its initial launch. Their final blog explained that they would have needed an “acquirer with an existing national fresh food supply chain” to continue its mission to create a luxury juice brand.

Lesson learned: User test your pricing and product before going to market, and respond to feedback.

4. Peppertap, raised $51.2 million

Founded in 2014, Gurgaon-based Peppertap was created with the mission to “revolutionize grocery shopping” as an Indian grocery delivery service with minimal charges. The mobile-first company operated with a 100% inventory-less model by partnering with local grocery stores, which made it particularly easy for geographic expansion.

However, according to Peppertap’s blog post detailing its successes and failures, there were a few problems with their mobile first approach. First, the integration of the mobile app and the partner stores was not seamless, bringing “too many stores online far too quickly.”

To build a large and loyal customer base, Peppertap was built on a discount model. Peppertap justified their losses with the end goal of massive customer loyalty and acquisition. Unfortunately, Peppertap was losing cash on every order and was set to run out of funding quickly.

Ultimately, Peppertap decided that closing doors “sooner (read while preserving a large amount of the capital we had raised) was better than later.”

Lesson learned: Prioritize your business model over customer acquisition and make sure it’s sustainable. Also, know when to close shop.

5. Sprig, raised $56.7 million

Healthy food startup, Sprig, closed its doors in May of 2017, proving that on-demand food delivery is a tough business.

At a $110 million valuation, Sprig’s demand maintained its growth, but Sprig’s CEO Gagan Biyani explained: “the complexity of owning meal production through delivery at scale was a challenge.” According to reports on Bloomberg, Sprig burned through $850,000 a month and was ultimately unable to find a buyer.

Partner at August Capital, Howard Hartenbaum, explained the reasoning behind the unsustainable business model to Bloomberg:

“It has become obvious that you can’t make money on individual deliveries; the cost of a single meal is too low to hide your associated fees. Who wants to subsidize a company with no path to profitability?”

The food delivery business has yet to prove itself to be sustainable with competitors like Munchery, Zesty, and Postmates all struggling.

Lesson learned: Profitability comes first.

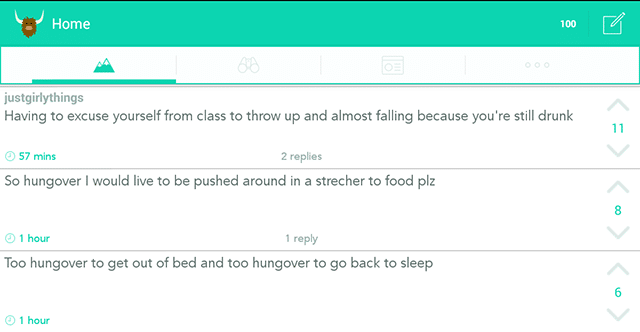

6. Yik Yak, raised $73.5 million

Founded in 2013, Yik Yak, the anonymous chat app took colleges by storm. Valued at $400 million at its peak, Yik Yak was unable to keep up with students as Snapchat took off.

Plagued by cyber bullies, threats, and cruel content, Yik Yak was even banned from some universities like College of Idaho. Along with its inability to pivot to group messaging, Yik Yak was unable to maintain its buzzworthy quality. By the end of 2016, app downloads declined 76% from 2015.

Yik Yak closed its doors April of 2017.

Lessons learned: Avoid falling into the “trend” trap.

7. Doppler Labs, raised $51.1 million

In business for four years, Doppler Labs wanted to “put a computer speaker and mic in everyone’s ear” with their product, Here One.

Manufacturing challenges pushed production longer than anticipated, meaning Doppler Labs wasn’t able to beat AirPods to the market or capitalize on holiday sales. To make matters worse, the new AirPods boasted a five-hour charge. Here One’s battery barely lasted two hours for music listening.

To get another product out the door, Doppler Labs would need to raise another $10 million. With plans to sell over 100,000 Hear Ones, only a disappointing 25,000 were sold. Underwhelming sales meant they were unable to raise more money to keep their business going.

Sales aside, Doppler Labs may have never had a chance. Perhaps founder Noah Kraft said it best:

“We fucking started a hardware business! There’s nothing else to talk about. We shouldn’t have done that.”

Doppler Labs was fighting an uphill battle being a small hardware company in the world of heavy hitters like Apple, Microsoft, Google, Amazon, and Facebook all working to develop their own products and in-ear devices. Hardware really is hard.

Lessons learned: Don’t start a hardware company. And if you do, your product better be better than the giants.