Africa has so much talent – we can’t even grasp it’: Angélique Kidjo on pop, politics and power by Emmanuel Akinwotu

She’s played with everyone from Tony Allen to David Byrne. Now the Grammy winner is singing with a new generation of African stars, celebrating their continent while confronting its failings.

n a video call from Paris, Angélique Kidjo, 60, shifts and leaps in her seat with the restive energy of a teenager. “I’m always changing and innovating and this album is no different,” she says. “Change brings life to things; it keeps me going. In life, you never know what to expect.”

Over a career that spans five decades, the Beninese artist has crossed paths with everyone from Gilberto Gil and Tony Allen to Talking Heads, Bono and Vampire Weekend. She has four Grammy wins in “world music” categories – second only to Ladysmith Black Mambazo.

On her new album, Mother Nature, her 15th, she takes sounds on which she has touched before – Cuban salsa, Congolese rumba, soul, jazz and west African musical traditions – and blends them with modern African pop, in collaboration with a younger generation of stars including the Nigerians Burna Boy, Yemi Alade and Mr Eazi and the Zambian rapper Sampa the Great. The songs on Mother Nature celebrate the continent’s cultural might and zeal, while exploring urgent themes from the climate crisis to police brutality. At an age when some singers might coast, Kidjo sounds like a woman armed with a loudhailer and a placard.

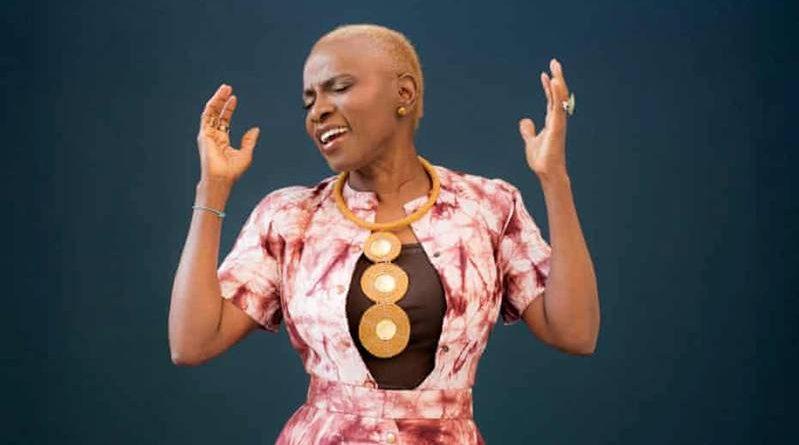

She sits in a dim rehearsal room, but brims with light, speaking to the screen as if trying to leap into it: “I can talk, talk, talk about music for hours, because I breathe it!” she says, her arms outstretched, looking stylish in a patterned khaki shirt, a black turtleneck, gold droplet earrings and cropped blond hair. She revels in the collaborations with those young artists, who call her “Mum”; the songs are intended to showcase the best of Africa. “They have something to say about where Africa is and where it is going,” she says. “This was really a delight – it gives me energy and a good feeling.”Advertisement

Free & Equal, a pulsing, beat-heavy track that protests against authoritarianism, came about after she saw Sampa the Great performing on YouTube. Other collaborations were built on personal relationships – and after some controversy.

Do Yourself, a feelgood rallying call for African pride sung in a mixture of English and Yoruba – “I’ve been on my knees but I don’t need help” – was written and co-performed by Burna Boy after he lost the award for best world music album at the 2019 Grammys to Kidjo. Her winning album, Celia, adapted songs from the Cuban salsa singer Celia Cruz – “one of my inspirations,” she says – drawing out the shared historical and musical synergy of west Africa, South America and the Caribbean.

When you are on stage you have to be naked spiritually

Burna Boy’s rival album, African Giant, was a blockbuster production (on which Kidjo collaborated) and to many a litmus test of whether the awards fully appreciated the recent traction of African pop. Amid collaborations with Ed Sheeran, Coldplay and more, he has led a wave of the continent’s pop singers out of a world music tag and into the global pop mainstream, so Kidjo’s win was seen by some as a conservative choice. She gracefully dedicated her win to Burna Boy and then went to console him.

“The week after the Grammys, I went to see him, because I was in LA. We had a conversation. I said: ‘Look, my first Grammy was after how many albums? It’s nothing against you, it’s just the way it works.’ He also deserved to win.” And he did, the following year. For years, she has lobbied the US music establishment to pay greater attention to African music. “I was telling them that the new generations are gonna take you by storm – and the time has come.”

Activism against political repression and state violence courses through many of the songs. The single Dignity, featuring the Afrobeats star Yemi Alade, draws on the #EndSars protests against police brutality that swept through Nigerian cities in October, in one of the largest demonstrations seen in the country for decades. Alade sings: “Soro soke, werey,” meaning “speak up, idiot” in Yoruba, echoing the slightly jovial yet demanding slogan of the movement.

The protests came to a halt after security forces shot dead at least 12 protesters on 20 October at a toll gate in the Lekki area of Lagos. Protesters livestreamed the events to hundreds of thousands of viewers, showing soldiers and police firing live rounds at the protesters, many of whom were singing the national anthem and were draped in the country’s flag. In the subsequent crackdown, thousands of people across the country were arrested and abused by security forces.

“I was watching what was happening and it was really affecting me,” Kidjo says. “I was thinking of my family in Lagos – and Lagos is just next door to Benin.” Despite the crackdowns, finding ways of speaking out in defiance is vital, she says. “It’s so important to keep making the demand that this is not the leadership we want. I’m offering this song with Yemi Alade as part of that conversation, that what is going on in Nigeria might happen in Benin. It might happen in Ghana, in Jo’burg, in Nairobi. Leaders, our leaders, don’t see that the only asset that can keep them in power is their population, not violence.”Advertisement

Her vociferous resistance is no mere sloganeering – in her youth, Kidjo actively opposed the communist dictatorship that ruled Benin from 1972 to 1991. Born in 1960, Kidjo had grown up surrounded by creativity, with a mother who ran a theatre troupe and who started Kidjo’s career at six by pushing her on stage when a lead actor was ill. But the repressive regime, established after a military coup, allowed space for only the narrowest kind of art. “Every artist was summoned to write propaganda – I refused,” she recounted later.

She left the country in 1983 and moved to Paris, releasing Logozo, her major label debut, in 1991. It immediately demonstrated her range, hopping from keening acoustic ballads to crisp funk-pop. The strictures in Benin meant she was musically voracious when she got out: in the 90s, she soared through Jimi Hendrix covers and Carlos Santana collaborations and began charting the musical links across the black Atlantic.

She has become a kind of anthropologist and a model of sound cultural exchange. It would be easy to see her 2018 re-recording of Talking Heads’ Remain in Light, an album in thrall to African rhythm, as simple reclamation, but she has heralded the “bravery” of the band’s creativity and framed her recording as part of a cultural conversation.

Our leaders don’t see that the only asset that can keep them in power is their population, not violence

“Music for me is like a language; it’s such a powerful, transformative thing and we share it and add to it. I’ve never let any boundary stop me from being creative and taking music further,” she says with an indignant passion, almost as if I had suggested otherwise.

While she has continued to champion artistic freedom, however, opposition groups and activists in her native country – now a presidential republic – have been systematically repressed. In a 2020 report, Amnesty found discrimination against women, minorities, journalists and health workers, restrictions on expression and “excessive force” from police.Advertisement

Across Africa, meanwhile, a resurgence in third-term presidential bids and efforts to change constitutions have been opposed by young populations that have grown weary of ageing, despotic leadership. “We’re seeing different examples of dictatorship in Africa, but also around the world, that we have to keep standing against, because this is our future,” she says. “We can’t just sit and watch. It’s up to us to act, to keep pushing further, to shape the future we want.”

Benin is fundamental to her music – and a rubric for exploring themes that resonate more widely in Africa. Omon Oba, a gently folksy song meaning “child of the king”, urges a pride in African identities, drawing on royal histories such as the Kingdom of Benin – a centuries-old area that imperial British forces violently subsumed into Nigeria in the late 19th century. The region is the source of the Benin bronzes, sculptures that still sit mainly in British and western institutions, amid growing calls for their return.

National and continental pride, she says, carries the obligation to do better than the preceding generation and tell the stories of these injustices. “Africa is a continent that has so much talent, wealth and potential. We know it and, at the same time, we can’t even fully grasp it yet,” she says. “We still have negative stereotypes. We are still documenting our histories. Some of it is, but much of our history is not yet written.” Music, for her, can be a form of history-telling. “It’s an oral transmission: it gives us a sense of belonging, a sense of identity and strength,” she says.

The climate crisis, which has had devastating effects in Africa and across the global south, has been at the front of her mind in recent years. “Africa is on the frontline of climate change – we’re seeing this, the devastation it’s causing. All people in Africa need to become more aware of this and there needs to be more leadership to face up to this,” she says. On the title track of her new album, she sings: “Mother Nature has a way of warning us / A timebomb set on a last countdown.”Advertisement

She says the pandemic is an example of the way our relationship to the environment has come into sharper focus. “You know we are all interconnected. What started in one place has spread absolutely everywhere, so the impact of our ways of life, our choices, affects us all. That’s why our solutions need to have unity. I’m always saying it over and over: we have to come together to solve our problems.”

She isn’t quite ready to give up flying, though – “I enjoyed one year of just going nowhere and now I can’t wait to go back on the plane, going around and around!” – but the pandemic caused her to reflect on the importance of touring and connections. “My mum used to say: when you are on stage, you have to be naked spiritually. You can’t pretend. You just have to do what you love to do, in the truth and the light of it.”

On stage, Kidjo often sings as if each word is a song in itself, with such care and strength of emotion. Nothing feels left behind. “When you are in that kind of mindset, you’re completely vulnerable and at the same time very powerful. So, when you are touring, you discover your smallness,” she says – your vulnerability, that is, and mortality. “You realise that anything can happen at any time and, when you go, that’s it.”

The vitality of her new pop sound suggests Kidjo is not at the end, but very much in the middle of her career – and is as driven as ever. A short film she has made, exploring how patriarchal dynamics within households in Benin are upended during crises such as the pandemic, will be shown at the Manchester international festival in July as part of Postcards From Now, an exhibition on the post-pandemic future. That month, she will also record a collaboration with Philip Glass, singing lyrics from David Bowie’s Lodger for Glass’s Symphony No 12, which premiered live in Los Angeles in 2019. “It’s a beautiful adaptation from David Bowie’s poetry and it’s such an honour, because they said they wanted only me to do it, for what I would bring to it.”

This work in the classical realm keeps evolving. “I’m doing a rehearsal with a classical piano player: we have a project called Love Words, singing only love songs. After this, I have a 24-hour break before I go to Prague to record with Philip Glass, then I have to go to New York because I have a show at the Kennedy Centre in June,” she says breathlessly. “I’m like: no, I need one day to rest, and they’re like: oooh,” laughing while mimicking her manager pulling her hair out. “It’s hectic now, but I love it. Music is my breath. I don’t think that I can do any other job.”

Mother Nature is released 18 June by Universal Music Group. Postcards From Now is at Manchester international festival from 1-18 July. Kidjo’s film will be available online for free during the festival.

By Emmanuel Akinwotu, TheGuardian