This is How Google will Collapse by Daniel Colin James, Hackernoon

Reporting from the very near, post-Google future

Google made almost all its money from ads. It was a booming business — until it wasn’t. Here’s how things looked right before the most spectacular crash the technology industry had ever seen.

The crumbling of Google’s cornerstone

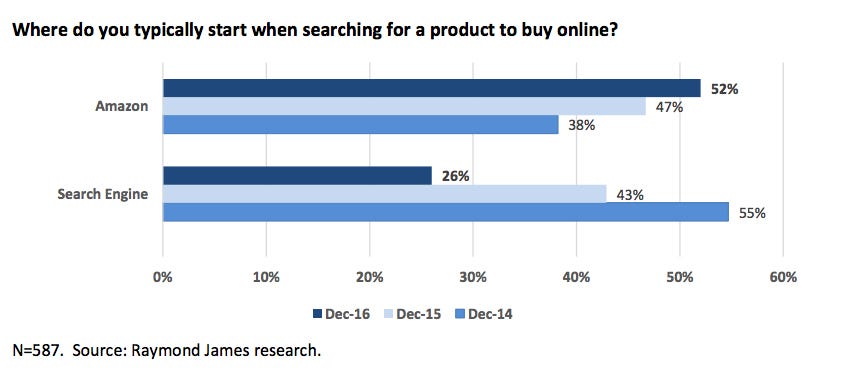

Search was Google’s only unambiguous win, as well as its primary source of revenue, so when Amazon rapidly surpassed Google as the top product search destination, Google’s foundations began to falter. As many noted at the time, the online advertising industry experienced a major shift from search to discovery in the mid-2010s.

While Google protected its monopoly on the dying search advertising market, Facebook — Google’s biggest competitor in the online advertising space — got on the right side of the trend and dominated online advertising with its in-feed native display advertising.

In late 2015, Apple — Google’s main competitor in the mobile space — added a feature to their phones and tablets that allowed users to block ads.

Devices running iOS were responsible for an estimated 75% of Google’s revenue from mobile search ads, so by making this move, Apple was simultaneously weighing in decisively on the great ad blocking debate of the 2010s and dealing a substantial blow to the future of online advertising.

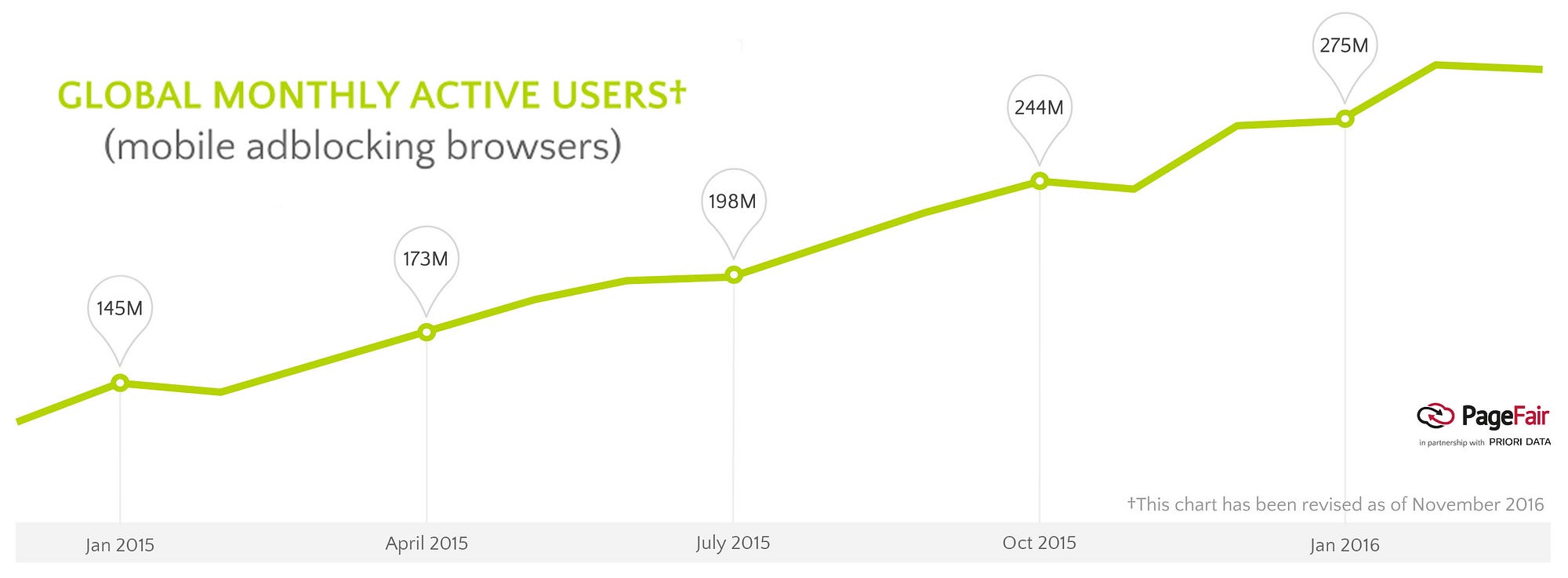

A year later, as the internet went mobile, so too did ad blocking. The number of people blocking ads on a mobile device grew 102% from 2015 to 2016; by the end of 2016, an estimated 16% of smartphone users globally were blocking ads when browsing the internet on a mobile device. The number was as high as 25% for desktop and laptop users in the United States, a country that accounted for 47% of Google’s revenue.

The people most likely to block ads were also the most valuable demographic: millennials and high earners.

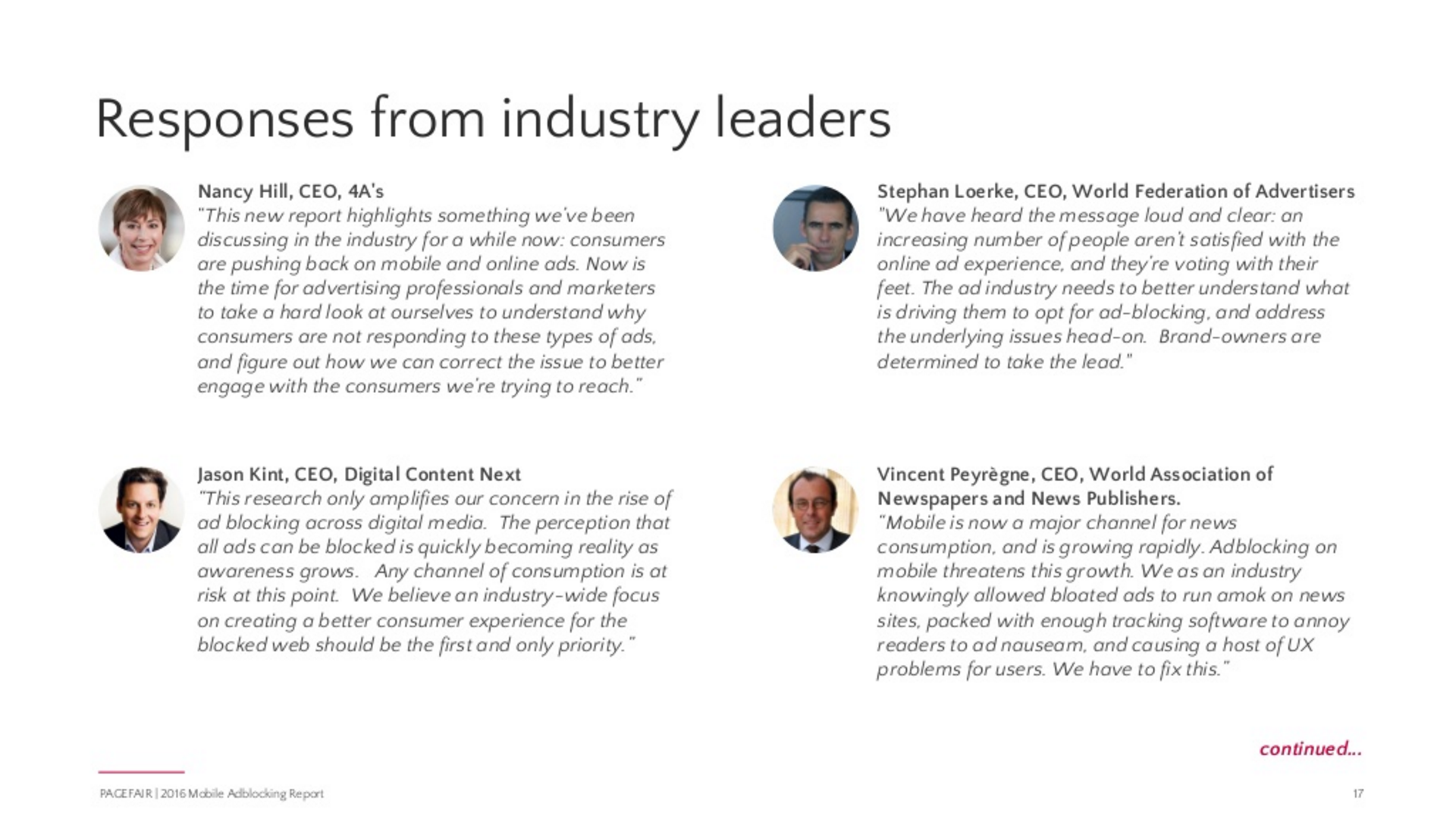

Internet users had spoken, and they hated ads.

In early 2017, Google announced its plans to build an ad blocker into its popular Google Chrome browser. Google’s ad blocker would only block ads that were deemed unacceptable by the Coalition For Better Ads, effectively allowing the company to use its dominant web browser to strengthen its already dominant advertising business.

Even after making this desperate and legally questionable move, it would quickly become clear to Google that even though ads were getting better, ad blocking numbers would continue to rise. Google had given even more people a small taste of what an ad-free internet experience could look like.

The company discovered that it wasn’t just annoying ads that people didn’t like; it was ads in general.

A key platform where Google served ads was YouTube, which it bought in 2006 and quickly turned into one of its biggest entities. But even with a sixth of the world visiting this video-sharing behemoth every month, YouTube never became profitable. In an attempt to combat the effect of ad blockers, YouTube launched an ad-free subscription model in late 2015, but the subscription numbers were underwhelming.

YouTube’s already insurmountable problems multiplied in early 2017 as advertisers began to pull out amid ad placement controversies, and huge revenue generators began to leave the site.

Even those who weren’t blocking ads had trained themselves to ignore them entirely. Researchers dubbed this phenomenon “banner blindness”. The average banner ad was clicked on by a dismal 0.06% of viewers, and of those clicks, roughly 50% were accidental.

Research showed that 54% of users reported a lack of trust as their reason for not clicking banner ads and 33% found them completely intolerable. These figures painted a pretty grim picture for the sustainability of online advertising, but especially for Google’s position within the industry.

Google’s mighty engine had started to sputter.

A chance to pivot, and how Google missed it

If losing a major portion of their audience and annoying the rest wasn’t bad enough, Google also failed to get ahead of one of the biggest shifts in technology’s history. They recognized the importance of artificial intelligence but their approach missed the mark. Since Google’s search pillar had become unstable, a lot was riding on the company’s strategy for artificial intelligence.

“We will move from mobile first to an AI first world.”

Google’s then-CEO Sundar Pichai famously predicted in 2016 that “the next big step will be for the very concept of the ‘device’ to fade away” and that “over time, the computer itself — whatever its form factor — will be an intelligent assistant helping you through your day. We will move from mobile first to an AI first world.”

Google’s ability to acknowledge the coming trend and still fail to land in front of it reminded many observers of its catastrophic failures in the booming industries of social media and instant messaging.

Google vs. Amazon

Meanwhile, in 2014, Amazon released a product called Amazon Echo, a small speaker that could sit in your home and answer questions, perform tasks, and buy things online for you. The Echo was a smash success. Google released its copycat product, Google Home, two years later, but it was already too late to catch up, and had no clear revenue strategy.

Alexa — the assistant that lived inside the Echo — on the other hand, was quickly integrated into several products and services, and its monetization model was clear, viable, and most importantly future-friendly. The Echo made it easy to order products through Amazon, and every time someone used an Echo to purchase something, Amazon made money.

Google extended the reach of their virtual assistant by building it into Android, but doing so still didn’t provide an answer for how the technology would generate enough revenue to sustain Google’s expanding repertoire of expensive innovations.

Google’s ads relied on screens, yet voice interaction subverted screens entirely. Google briefly tried playing audio ads with the Google Home, but consumers were far from receptive. Investors started to voice their concerns in 2017, but Sundar Pichai told them not to worry, leaving them to assume that Google would use their age-old strategy and analyze users’ voice searches so that users could be shown more suitable ads on devices with screens.

Headlines in early 2017 proclaimed that “Alexa Just Conquered CES. The World is Next.” Amazon then made their technology available to third party manufacturers, putting even more distance between the two companies. Amazon had already beaten Google once before, holding 54% of the cloud computing market (compared to Google’s 3%) in 2016, and they were just getting started.

By early 2017, Amazon had begun closing in on the entire retail industry.

Ads weren’t forever

At its peak, Google had a massive and loyal user-base across a staggering number of products, but advertising revenue was the glue that held everything together. As the numbers waned, Google’s core began to buckle under the weight of its vast empire.

Google was a driving force in the technology industry ever since its disruptive entry in 1998. But in a world where people despised ads, Google’s business model was not innovation-friendly, and they missed several opportunities to pivot, ultimately rendering their numerous grand and ambitious projects unsustainable. Innovation costs money, and Google’s main stream of revenue had started to dry up.

In a few short years, Google had gone from a fun, commonplace verb to a reminder of how quickly a giant can fall.

From a quick cheer to a standing ovation, clap to show how much you enjoyed this story.

By Daniel Colin James, https://hackernoon.com