The impact of COVID-19 on journalism in Emerging Economies and the Global South

Thomson Reuters Foundation has a release a report on the the impact of COVID-19 on journalism in Emerging Economies and the Global South. The report is the work of 55 alumni of various training programmes run by the Thomson Reuters Foundation (TRF) who shared their experiences about living – and working – in the COVID era. These insights, coupled with extensive desk research and analysis, inform the narrative of this new report.

The 72 page report is authored by Damian Radcliffe, a Carolyn S. Chambers Professor in Journalism and a Research Associate of the Center for Science Communication Research (SCR), at the University of Oregon.

The report concludes by observing that COVID-19 has had a twin impact on journalism: not only has it presented a unique set of challenges for journalists, but it has also accentuated and accelerated several major structural issues that predate the pandemic.

These issues include encroachments on press freedom, the news industry’s faltering business model, the erosion of trust in journalism and combating fake news.

It further states that Laws banning ‘fake news’ can be used as instruments to support government crackdowns on media freedom and on reporting with which political elites disagree. The pandemic has offered a justification for more countries to introduce these types of laws, tighten current restrictions or suspend existing laws.

Even if these developments are rolled back, journalism and the news industry is unlikely to return to its pre-pandemic state. Many of the jobs and outlets that have been lost will never reappear, and those that do may look very different to the way they were.

We do not know what the long-term impact of the coronavirus will be on journalism, the news industry or our world as a whole. However, we do know that the impact of the COVID crisis has already been significant.

Even with vaccination programmes on the horizon, COVID-19 will continue to play a major role in our lives, as well as in the work that journalists do – and how they do it – for a long time to come.

Here are some of the main themes featured in the report:

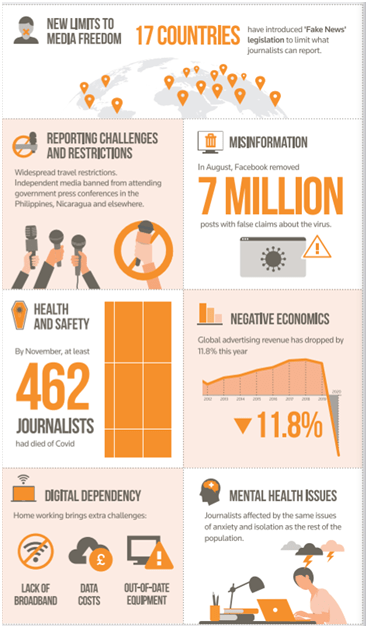

New limits to media freedom

There are concerns that the COVID crisis is being used to curb media freedoms around the world. This is taking numerous forms, including limiting access to information, attacks on journalists, government closures of news media and new laws that limit press freedom. The Austria-based International Press Institute (IPI) has identified 17 countries that have passed ‘fake news’ regulations since the COVID-19 outbreak began, giving them broad-ranging powers that can reduce the ability to cover the crisis. RSF (Reporters Without Borders) argues these types of COVID-triggered “emergency laws spell disaster for press freedom”, noting how “weapons of repression against individual journalists as well as news organisations have been greatly strengthened in many countries” and adding that “the arsenal of sanctions has been hugely expanded”.

R e p o r t i n g c h a l l e n g e s a n d r e s t r i c t i o n s

The Center for Media Data and Society at the Central European University has shared how independent media have been banned from attending government news conferences in countries such as Nicaragua and the Philippines. As countries went into lockdown, many nations implemented curfews and travel restrictions. Although, while working, some journalists might be able to bypass these constraints, this has not always been the case. “In the Philippines,” Meera Selva at the Reuters Institute recounts, “the President’s office banned all journalists from travelling to areas in lockdown without a specific identification card issued by his communications office.” Elsewhere, there are concerns about access to data, and that coronavirus deaths have been under-reported. As The Economist explains, official statistics may “exclude victims who did not test positive for coronavirus before dying – which can be a substantial majority in places with little capacity for testing”.

Misinformation and the ‘infodemic’

There is a hunger for information about this new virus among members of the public. However, especially in the early days, there has also been a great deal of confusion about the nature of this novel coronavirus and the best ways to respond to it. Journalists continue to face a number of challenges in combating the ‘infodemic’, including the speed with which misinformation travels, propagation by public officials and figures, and having the skills to discern fact from fiction. Obstruction and obfuscation on the part of public bodies can also make a journalist’s job harder and, in this vacuum, misinformation can flourish. In many cases, that activity takes place on social networks and private messaging services, like WhatsApp. In August, Reuters reported that Facebook had removed more than seven million pieces of content with false claims about the virus. However, these are only posts deemed to risk imminent harm. Conspiracy theories, hoaxes and false information may be identified on the social network yet remain in place.

Health and Safety

In a new report published in September 2020, UNESCO found that between January and June this year “journalists have been increasingly attacked, arrested and even killed”. These attacks don’t just come from politicians and public figures. They also come from members of the public, in person or online, with their actions emboldened by the anti-press rhetoric deployed by increasing numbers of politicians and other critics. The Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) highlighted how, in the early days of the pandemic, violence against journalists reporting on lockdowns could be seen in many countries, with journalists often being specifically targeted while they were doing their job. Journalists have also faced further challenges in terms of access to personal protective equipment (PPE) and training on how to report safely during a pandemic. As the Geneva-based Press Emblem Campaign (PEC) reminds us: “Journalists are at great risk in this health crisis because they must continue to inform, by going to hospitals, interviewing doctors, nurses, political leaders, specialists, scientists, patients.” By 15 November 2020, according to the PEC’s data, at least 462 journalists had died from COVID-19 in 56 countries. Within this, the highest number of journalists killed by coronavirus can be seen in Peru, with 93 reporter deaths. Hugo Coya, the former president of Peru’s public television and radio institute, (IRTP) reflected that “journalists are expected to go to the frontline but they weren’t trained how to protect themselves from points of contagion”.

Negative Economics

COVID-19 has accelerated long-term financial trends that have beset journalism, in particular newspapers, for some time. Reduced revenues, particularly advertising income, have contributed to the closing of news outlets, as well as major job losses, pay cuts and furloughs. There’s an irony here in that this financial free fall comes at a time when – in the early stages of the pandemic at least – many news outlets and media platforms have been enjoying record traffic. This consumption, however, was not enough to offset declines in revenue primarily caused by a sudden advertising downturn. Some commentators initially predicted that the pandemic could create an “extinction-level event” for the media industry around the world. These fears now look somewhat overblown. But, whatever the outcome, it’s clear the news industry that emerges on the other side of this crisis will look very different from the one that went into it. Although few journalists have been immune from these impacts, freelancers may be among the hardest hit. Reduced opportunities, a broader freelance pool (due to laid-off journalists going freelance) and the rates paid by in-country media outlets (as opposed to international news organisations) are among the factors affecting this demographic .

Digital Dependency

For journalists who have remained employed, the physical closure of most newsrooms has presented a series of unexpected difficulties. This includes access to reliable broadband connections, high data costs, unsuitable equipment, power outages and having to negotiate new ways of working. That many journalists are also having to do this on reduced pay – and often with increased costs as a result of high data charges – has merely added to their stresses. At the same time, there have been some potential benefits to this situation, such as the growth of online output, development of digital skills and opportunities to engage in online delivered training .

M e n ta l H e a lt h a n d W e l l b e i n g

COVID-19’s influence on incomes, job security, work habits and locations, doubts about the effectiveness of public health advice and policies, alongside the spread of fake news, and concerns about an unclear future, impact on everyone. Journalists included. These anxieties do not look likely to ease anytime soon, and many journalists reporting on the coronavirus will continue to see their personal experiences of the pandemic closely entwined with the stories that they are covering. Because of this, it’s more important than ever for journalists to look after their physical and mental health. Acknowledging this, Dr Cait McMahon, Director of the Dart Center Asia Pacific, cautions that reporting on the coronavirus is “different to you going to work on a story that’s happened to someone else, which you may or may not have experienced”.

You can download the full report here.